It’s a rare moment when a proposed law reshaping the mental health landscape receives unprecedented support. It’s even more stunning when it’s enacted within eight months. This is what occurred after Gov. Gavin Newsom laid out his CARE Court proposal.

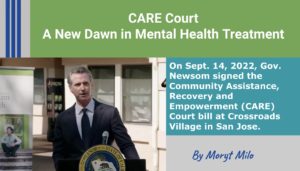

On Sept. 14, 2022, Gov. Newsom signed the Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment (CARE) Court bill at Crossroads Village in San Jose. The CARE Act will completely reshape the way those with severe mental illness receive treatment.

“Just a few months ago, I stood here and we laid out a vision, and a marker and a dream, and here we are and we made it a reality,” Newsom said.

CARE Court focuses on individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Individuals who are often homeless or incarcerated. The new law will make it easier to divert them into community-based treatment instead of jails due to misdemeanors like trespassing and petty theft.

CARE Court could also be a next step after a 72-hour hold (5150) or a 14-day involuntary stay (5250) as part of a continuum of care. The objective is to eliminate the constant cycling of an individual through the hospital and jail systems where treatment is minimal and insufficient. The program is also aimed at getting individuals living untreated off the streets and into care.

The program is structured to provide court-ordered comprehensive treatment, housing, and supportive services for severely mentally ill individuals for one year, with the option to extend it for another 12 months. For the first time, families will have a proactive say in a loved one’s care. In the past, families had no input unless the individual in crisis gave consent.

This shift enables a family member to petition the court for treatment and serve as an advocate, supporting the individual as he/she works toward stability and recovery.

There are others authorized to petition the court, as well, including first responders, social workers, clinicians, and medical professionals.

Newsom said the state has tried continuously to reform the mental health system and nothing has worked. The only option left was to change the system in its entirety to help the state’s sickest population. It is inhumane to leave people on the streets to suffer or die, he said.

He pointed out that even after the state enacted Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT), only 218 people were treated last year in a state with 40 million people.

“That isn’t good enough. This is why we need CARE Court,” he said.

The Money and the System

The state is committing billions to the program. It already approved $14.7 billion in funding for a spectrum of housing services and $11.6 billion in funding for county behavioral health services. Newsom is adding $63 billion to help roll out the program and $1.4 billion to help rebuild the state’s severe shortage of social workers, counselors, and staff.

The program’s success will take time and there are concerns. Unlike AOT, also known as Laura’s Law, which let counties choose to opt-in, CARE Court is mandatory. If a county fails to comply, it could be fined from $1,000 a day up to $25,000 per violation.

Santa Clara County Supervisor Susan Ellenberg said, “Building out all levels of continuity of care and expanding services through CARE Court will be great.”

But such a commitment puts all the weight on the county’s shoulders, especially when it comes to housing requirements, she said. “The county is not in the business of doing housing,” Ellenberg said.

“The cities need to expedite permitting and zoning for permitting of mental health infrastructure. We can’t do it alone. We need the cities as our partners.”

Counties will also have to carve out a new court system for CARE Court, and there will be growing pains.

As the bill was moving through the state legislature, state Sen. David Cortese said judges brought up issues related to staffing, especially qualified case workers. CARE Court will rely on social workers and clinicians to review each case to determine who qualifies for the program. That workforce rebuild will take time. Equally so will be the demand for enough beds and long-term care facilities. All of which will be needed to accommodate CARE Court’s requirements.

Most importantly, Cortese said the way we treat people now, putting them in jail for treatment, is fundamentally wrong and must change.

“This program is designed to treat people before a crisis happens. We can’t keep jailing people because there is nowhere else for them to go for help. We can’t keep criminalizing mental illness,“ he said, referring to the fact that the country’s prison system has turned into the nation’s largest mental health hospital system.

Seven counties will pilot the CARE Court program starting Dec. 1, 2023. Santa Clara County falls into the second group beginning Dec. 1, 2024. This could work to the county’s benefit, Ellenberg said.

“It will be significant because we can learn from their experiences and challenges, and where to cover the gaps,” she said.

For the governor, the rationale behind the passage of CARE Court was simple. “Currently, these people are no longer on the streets because they’ve died,” he said.

“I want to be able to say they are off the streets because they were saved.”

To learn more about CARE Court, click here.